US Quiz of the Month – February 2021

CASE REPORT

A 69-year-old woman without relevant past medical history presented with anorexia, jaundice and weight loss for the past 2 months. An abdominopelvic CT scan showed a 4 cm mass of the pancreatic head, along with the double duct sign. This finding was confirmed by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), revealing an hypoechogenic, heterogeneous, ill-defined solid nodular lesion with 33 x 38 mm, contacting with the splenoportal venous confluence and with the superior mesenteric vein (Fig. 1 and 2).

Figure 1. EUS: pancreatic lesion contacting with the splenoportal venous confluence and with the superior mesenteric vein.

EUS-guided fine-needle biopsy (FNB) using a 22G needle was performed (2 needle passes; AcquireTM Endoscopic Ultrasound FNB Device, Boston Scientific).

Figure 2. EUS: EUS-guided FNB of the pancreatic lesion.

WHAT IS THE MOST LIKELY DIAGNOSIS

DISCUSSION

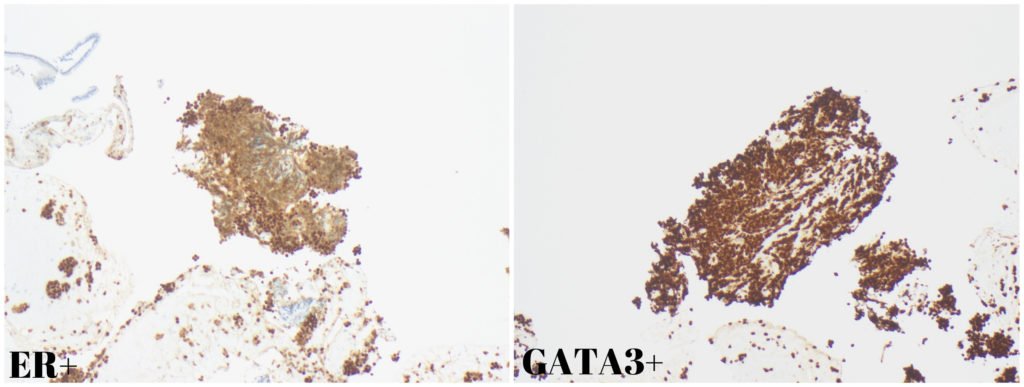

Although pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is the most common solid pancreatic lesion, EUS-guided FNB revealed a different diagnosis. Pathology found cell nests consistent with a poorly differentiated carcinoma, ER+ and GATA3+ (Fig. 3), raising the possibility of a breast primary.

Figure 3. Pathology: Diffuse nuclear positivity for ER and GATA3.

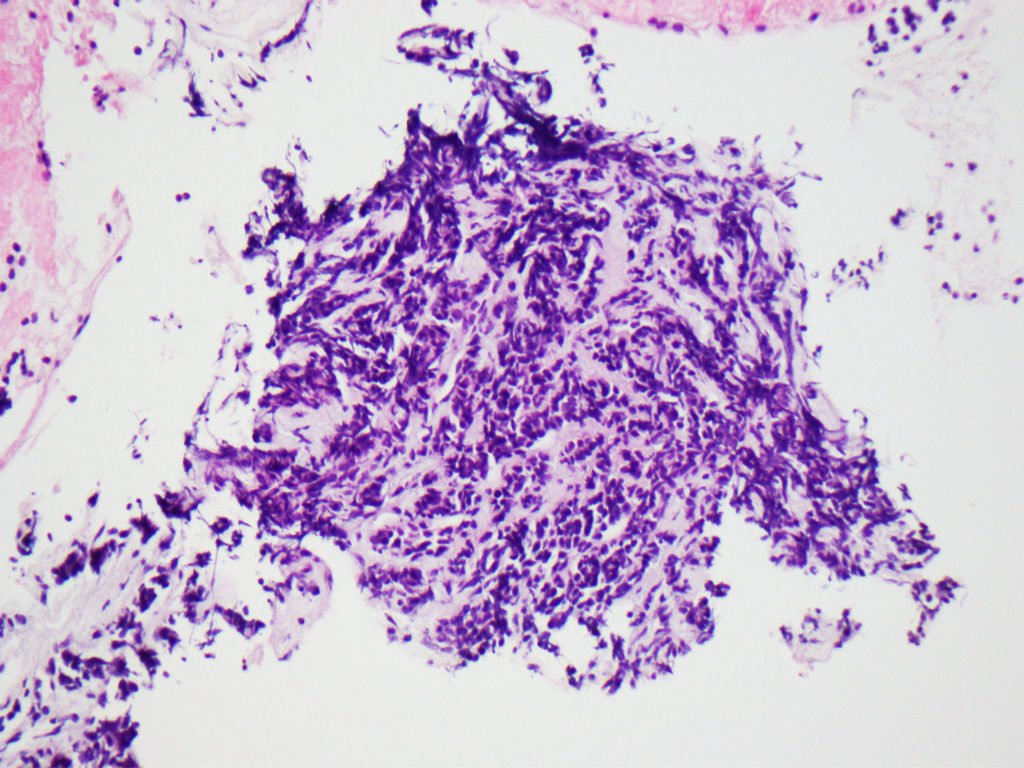

A thoracic CT, done for staging purposes, surprisingly found a multilobulated irregular mass of the left breast. Biopsy of this lesion showed an invasive lobular carcinoma (Fig. 4), which overlapped morphologically with the pancreatic lesion, thus enabling the diagnosis of pancreatic metastasis secondary to invasive lobular carcinoma (oligometastatic breast cancer).

Figure 4. Pathology: Lobular carcinoma in a desmoplastic stroma.

After multidisciplinary discussion, the patient was started on chemotherapy and hormonal therapy followed by pancreaticoduodenectomy and breast surgery.

Up to 10% of solid lesions initially thought to be adenocarcinoma are latter diagnosed as other pancreatic conditions.[1] Therefore, EUS-guided tissue acquisition should be always considered in patients with a pancreatic solid mass in order to establish the pathological diagnosis, thus potentially changing patient management and reducing the number of unnecessary surgeries for other conditions that mimic pancreatic adenocarcinoma (e.g. autoimmune pancreatitis, focal chronic pancreatitis, lymphoma, and pancreatic metastasis).

Pancreatic metastasis are rare, accounting for only 2% of all pancreatic malignancies.[2] The most common primary cancer responsible for pancreatic metastasis is, by far, renal cell carcinoma, followed by colorectal cancer, melanoma, breast cancer, lung carcinoma, and sarcoma.[2] It may be difficult to differentiate pancreatic metastasis from a primary pancreatic tumour since both the clinical presentation and radiological characteristics are similar.[2,3] Therefore, histopathology plays a key role in the diagnosis of this entity. Patients with pancreatic metastasis should be evaluated with a multidisciplinary approach, being surgery part of the multimodality treatment of these clinical entities. The usefulness of surgery is mainly linked to the biology of the primary tumours, and its often advocated when the lesion is single and for patients fit to perform a pancreatectomy.[2] An improvement in patient survival has been observed for metastases from renal cell cancer, while for other primary tumours the role of surgery is mainly palliative.[2] However, even in the case of pancreatic metastases from breast cancer, an aggressive surgical approach appears useful for good palliation in selected patients with a limited pancreatic disease.[2]

REFERENCES

- Abraham SC, Wilentz RE, Yeo CJ, Sohn TA, Cameron JL, Boitnott JK, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple resections) in patients without malignancy: are they all ‘chronic pancreatitis’? Am J Surg Pathol. 2003 Jan;27(1):110–20.

- Sperti C, Moletta L, Patanè G. Metastatic tumors to the pancreas: The role of surgery. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology 2014; 6:381.

- Boudghène FP, Deslandes PM, LeBlanche AF, R. Bigot JM. US and CT Imaging Features of Intrapancreatic Metastases. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography 1994; 18:905–10.

AUTHORS

Rui Mendo1, Joana Carmo1, Daniel Pinto2, Martinha Chorão2, Cristina Chagas1.

- Gastroenterology Department, Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Ocidental, Hospital de Egas Moniz, Lisbon, Portugal.

- Pathology Department, Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Ocidental, Lisbon, Portugal.