US Quiz of the Month – Setembro 2024

Case Report

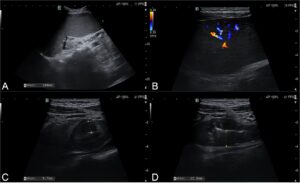

We present the case of a 40-year-old female patient referred to our center with a 1-month history of fatigue, abdominal pain and distension, which suddenly worsened. Her past medical history includes one episode of facial angioedema during this period. Laboratory analysis showed mild pancytopenia, with white blood cells of 3.6 x 109/L (normal 3.9-10.2 x 109/L), hemoglobin of 10.7 gr/dL (normal 12.0-16.0 gr/dL), and platelet count of 148 x 109/L (normal 150-400 x 109/L). The abdominal ultrasound (US) revealed marked splenomegaly with parenchymal hypervascularization, hepatomegaly, and a loop located in the epigastric topography, likely corresponding to the proximal small bowel, with irregular wall thickening (maximum of 12 mm), some loss of the normal stratification, in an extension of around 15 cm. It was associated with mesenteric fat hypertrophy, but no adenopathies were observed (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – US images (A and B) Splenomegaly with parenchymal hypervascularization. (C and D) Intestinal loop located in the epigastric topography, apparently corresponding to the proximal small bowel, with irregular wall thickening (maximum of 12 mm) and some loss of the normal stratification, associated with mesenteric fat hypertrophy.

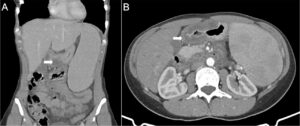

Subsequently, the patient underwent a computed tomography (CT) scan, which confirmed hepatosplenomegaly without swollen lymph nodes in the abdomen. The CT also showed parietal thickening of the gastric antrum, duodenal arch, and proximal jejunum, with mucosal enhancement and submucosal hypodensity (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – CT scan images (A and B) Hepatosplenomegaly and parietal thickening of the gastric antrum (arrow), duodenal arch, and proximal jejunum with mucosal enhancement and submucosal edema.

Upper endoscopy was unremarkable except for duodenal mucosal edema (Figure 3). Gastric and duodenal biopsies were normal.

Figure 3 – Upper endoscopy images (A) Normal gastric mucosa. (B) Edema of the duodenal mucosa.

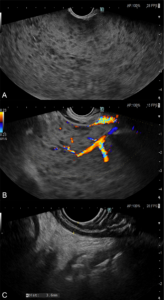

Thus, an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was performed, which excluded gastric or duodenal wall thickening and revealed massive splenomegaly with parenchymal heterogeneity, multiple hypoechogenic foci, and intense vascularization (Figure 4).

Figure 4 – EUS images (A and B) Massive splenomegaly with parenchymal heterogeneity, multiple hypoechogenic foci, and intense vascularization. (C) Normal wall thickening of stomach and duodenum.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

Posteriorly, the patient underwent a PET scan which only revealed splenomegaly with diffuse increased uptake of 18F-FDG. The peripheral blood and bone marrow examination suggested the diagnosis of splenic marginal zone lymphoma (SMZL). The complement component 4 level was low at <0.03 g/L (normal 0.15-0.57 g/L), C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) protein level was low at 0.006 g/L (normal 0.210-0.390 g/L), and C1-INH protein function was low at 24.6% (normal >68%).

These findings were compatible with gastrointestinal angioedema due to acquired C1-INH deficiency associated with underlying SMZL. The patient started rituximab and remain asymptomatic at 2-months of follow-up. The re-evaluation abdominal US was unremarkable, except for mild splenomegaly.

Discussion

We report a rare case of SMZL presenting with acquired gastrointestinal and orofacial angioedema due to C1-INH deficiency, manifesting with massive splenomegaly, pancytopenia, and abdominal pain.

It has been proposed that clonal proliferation of B cells in SMZL leads to the production of C1-INH neutralizing autoantibodies. Loss of inhibitory control of the kallikrein-bradykinin pathway and the classical complement pathway caused by low levels of C1-INH then results in attacks of angioedema1,2.

In contrast to cutaneous angioedema, gastrointestinal angioedema could be challenging to diagnose as patients often present with nonspecific imaging exams and symptoms (like acute abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea)1,2. Digestive US can provide very important information as a screening method, like in our case, showing nonspecific bowel thickening in addition to massive splenomegaly. Other findings can be found, namely, thickened mucosal folds and free fluid. Combining US with CT and EUS findings enhances the diagnostic accuracy. The resolution of these findings on subsequent imaging further supports the diagnosis3,4.

The clinical manifestations of angioedema can precede and obscure the diagnosis of a lymphoproliferative disorder so clinicians should be vigilant. Screening and treatment of the underlying disease often result in partial or complete remission of angioedema5,6 as in our case.

References

1 – Holguín-Gómez L, Vásquez-Ochoa LA, Cardona R. Angioedema [Angioedema]. Rev Alerg Mex. 2016 Oct-Dec;63(4):373-384.

2 – Pal NL 3rd, Fernandes Y. Intestinal Angioedema: A Mimic of an Acute Abdomen. Cureus. 2023 Feb 4;15(2):e34619.

3 – De Backer AI, De Schepper AM, Vandevenne JE, et al. CT of angioedema of the small bowel. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(3):649–652.

3 – Nzeako UC. Diagnosis and management of angioedema with abdominal involvement: a gastroenterology perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Oct 21;16(39):4913-21.

5 – Castelli R, Wu MA, Arquati M, et al. High prevalence of splenic marginal zone lymphoma among patients with acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency. Br J Haematol. 2016;172(6):902–908.

6 – Thongtan T, Deb A, Bedanie G, et al. Intestinal angioedema caused by an acquired C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency associated with underlying splenic marginal zone lymphoma. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2021 Feb 22;34(4):519-520.

Authors

Luís Santos1, Pedro Rocha1, Margarida Ferreira1, Pedro Amaro1, Pedro Figueiredo1,2

1 – Gastroenterology Department, Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra, Unidade Local de Saúde de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

2 – Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal